Opera Review: A Thrilling Lear at Paris Opera

Lear

Music by Aribert Riemann

Libretto by Claus Henneberg (after Shakespeare)

Conducted by Fabio Luisi

Directed by Calixto Bieito

Starring Bo Skovhus

Palais Garnier

Opéra Nationale de Paris

November 24, 2019

I first saw Lear by German composer Aribert Rieman

(b. 1936) at the San Francisco Opera back in the early 1980s, not long after

its world premiere in 1978. I was fairly new to opera then, but was impressed

by its drama and colorful modernist score. Since then, I have become much more experienced

in both twentieth century opera and in Shakespeare’s King Lear, which I’ve

see twice during the last year, neither in a quality production. King Lear

has proved amenable to adaptation, most famously by Japanese director Akiro

Kurosawa's film Ran, where the drama is memorably transported to feudal Japan

in a movie that is on my top 10 list. Rieman’s operatic adaptation, revived by

the Paris Opera the past few years, was even more memorable this time around,

and I think Lear deserves ranking among the great operas of the last

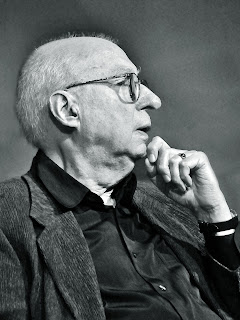

century. Rieman (pictured below) wrote 10 operas and 12-15 big orchestra pieces, but remains

rather unknown in the US. After initial debut runs in Munich, Paris, London,

and San Francisco Lear, like so many modern works, vanished from the

repertory. It should not. The opera sticks closely to the Shakespearean text

and is filled with orchestral and vocal thrills. The best analogy I can make is

to Alban Berg’s great early century operas Lulu and Wozzeck. All

these operas use the serial and atonal styles so characteristic of that era,

but use them to achieve spine-tingling emotional impact, rejecting any type of academic

abstraction or disregard for audience emotions. Riemann actually ups the ante

on Berg. Lear’s score is formidably complex, sometimes dividing the

strings into 40 (!) parts, but this is audible and exciting to hear, as the

dissonant string passages evoke a complex version of the Psycho score,

matching King Lear’s descent into madness. Many of the characters are given

distinctive themes, rather like Wagner's leitmotifs, and this helps us follow their

emotions and motivations. More than any of the recent staged King Lear’s

that I have seen lately, this opera gave me the mixed gut check of fear,

anxiety, sympathy, and sadness built into the play---exactly the emotional amplification

that opera should perform. This opera should be revived, and often. It is a

crime that the Metropolitan Opera has not staged it.

This production was designed by bad boy “Quentin Tarantino-type”

director Calixto Bieito, known for his outrageous takes on standard repertory,

such as torture and rape during Il Trovatore, singing men on the toilet

during Un Ballo in Maschera, and Mozart’s Abduction from the Seraglio

with actual prostitutes. Here he was more restrained, even conservative. The

set was mostly black, with characters in modern office dress. The minimalist

take focused the production on the characters themselves, a good choice since the

music and acting were so fine. The only odd bit was an enormous screen behind

the stage which slowly panned over the full body of both a naked man (the vulnerable

Lear?) and a munching camel (??). This was far better than the flamboyant set

by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle for the 1978 debut, which featured huge swaying

platforms that were impressive, but overwhelmed the drama. Here it seemed that

the production staff trusted the opera to succeed without Star Wars

effects. One way to make a modern opera more performed is to create an

effective, but non-extravagant set that can travel well and meet a budget, and

Mr. Bieito succeeded here.

57 year old baritone Bo Skovhus was a bit too young and buff

for the role, but acted and sang well, and conveyed Lear’s decline into madness

effectively.

Each of Lear’s daughters has a big role, and the standout was the

evil Goneril of Wagnerian soprano Evelyn Herlitzius, normally busy with Isolde

and Elektra, but here portraying a full-throated sociopath. The composer is great

in writing the three sisters with contrasting voices—Regan has a lighter, but

still domineering voice compared to her older sister, while the young, wronged

Cordelia is set as a light, coloratura soprano to convey innocence. I wish

there had been more writing for the Fool, played in all-white body makeup in an

eerie speech-sung style by Lucas Prisor. I think the writers missed an

opportunity here. While in Shakespeare Cordelia and the Fool were played by the

same actor, meaning long disappearances for one or the other character during

the drama, an adaptation need not face this limitation, so could have fleshed

out the part of the Fool, a compelling figure here. The orchestra played the

difficult score with distinction, and conductor Fabio Luisi has clearly benefited

from multiple performances in recent years to bring nuance and shape to the

music. This was an outstanding performance of a thrilling opera that has a classic

plot and theme well known to theater goers. Company directors should get over

their conservative fears of atonal twentieth century music and perform it,

often.

Comments

Post a Comment