Opera: L'Amour de Loin at the Met--Stimulating Contemporary Opera

When Wagner's Tristan und Isolde premiered in 1865, it pioneered the daring idea that an opera could have a minimal plot and still be compelling. It was followed by similar works in Debussy's Pélleas et Mélisande (1902), Messiaen's St. Francis of Assisi (1983), and now the compelling L'amour de loin (Love from Afar) by Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho. These works have a number of things in common. All tell an unconventional love story: Tritsan and Isolde meet as opponents but are swept up by a love potion; Pélleas and Mélisande veer between sibling-like and romantic love as part of a love triange; St. Francis is in love with God; and Jaufré and Clémence, the two lovers of L'amour de loin are separated by the sea (i.e. love from afar) and barely meet in life before the troubadour Jaufre dies, having fallen sick on his sea voyage to find her. All have the "female" protagonist end in some hybrid of love and death: Isolde's a musical Liebestod, Mélisande in childbirth, St. Francis swooning in religious ecstasy, and Clémence leaving the corporeal world to become a nun. While love and death (and their derivatives jealousy and revenge) are certainly operatic staples, they have rarely been so mystically and unconventionally melded as in these operas. In addition, all these operas push their affect to extremes using striking musical language that often defies the usual hyper-dramatic operatic stereotypes.

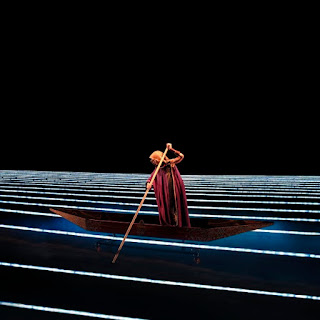

L'amour de loin has one of the better performance records for contemporary opera, with over ten productions following its premiere at the Salzburg Festival in 2000. Ever conservative, the Metropolitan Opera now gets to it 16 years later, but to its credit lavished a wonderful production on the opera. Through most of the opera the distant lovers, who learn of each other only via the Pilgrim who ferries back and forth (sort of a pre-internet dating site) are separated by the sea. In this production the separating sea is physically dominant, portrayed throughout by horizontal parallel laser light strings that completely occupy the massive Met stage from front to back, apparently about 5 feet above the stage itself, and even extending over the orchestra pit. Boats and birds portrayed in relation to this set are simple, almost cartoon-like in their spare design, increasing one's focus on the abstract sea:

These computerized lights can achieve a dazzlingly infinite range of color: sunset, storm, midday, etc. The chorus lurks below these lights (often with heads visible with vague amber lighting, like we are seeing them in the depths of the sea). But when they sing their heads pop up above the lights from below like singing mermaids as they act their main role as a Greek chorus admonishing the lovers. This was perhaps the most technically adept use of modern technology to suit and create an operatic mood that I have seen--here infusing the set with an ever-changing color palette that coordinated precisely with the music and plot. It's great to see that the Quebecois director and designer Robert Lepage has this brilliance in him, after the high-visibility failure of his recent Met Ring of the Nibelung with it's infernal machine that dominated the opera, stage, and action to poor use. Strikingly, in this opera the technical lighting-machine did not come across as a gimmick, overwhelming or diminishing the singers, who were often raised above the "sea" with a small elevated ship-like platform on a crane that reminded me of the old Myst games. Note the chorus' heads sticking above the water at left:

Composer Saariaho is one of a group of prominent Finnish composers prominent in contemporary music, and perhaps the most famous female composer now going. She has had a very visible New York season, with a recent concert by the New York Philharmonic of Sensurround pieces in the Park Avenue Armory (see my review here). She relies more on timbre and color than on melody and rhythm to achieve her purpose (similar to Debussy), and there were times, especially in the largely event-less first half, that my mind wandered, as it did at times in the NY Phil orchestra concert. Her music is very modernist in harmony without edginess--such edge might have been occasionally helpful for variety. The program notes described some use of medieval composition technique (e.g. organum with parallel fifths) but this was not at all obvious in the sound-world that emerged. When composers rely largely on color for expression, there is a great challenge in long pieces (like operas) to maintain interest--this challenge was faced in all four of the operas mentioned above. Of these, Wagner and Messiaen were not reluctant to use rhythm or the occasional big tune to bring an act to it's climax, e.g. the end of each act of Tristan or the end of St. Francis, but Debussy and Saariaho are less inclined to such extroversion. So how do they avoid boredom in a 2-3 hour opera?

I think that this opera succeeded best in the second half, when Jaufré journeys over the sea, at last meets his previously-imagined love, then dies. This included some plot elements that moved the opera forward--his dream of seeing her (wonderfully achieved with the soprano and a dancer-double emerging in and out of the water, lit like a hologram), a sea interlude akin to Debussy's La Mer or Britten's from Peter Grimes. Here there was more varying rhythm in the music, and the parallel sea-lights started heaving and moving vertically like waves to spectacular effect--the Met should have issued Dramamine! It was at these moments that Saariaho best achieved Wagner's concept of Gesamtkunstwerk--the unity of music, plot, lyrics, set, lighting to create one theatrical organism. These segments of the opera may have been the best I have seen of this ideal. Wagner's music tends to overpower the other elements, while Saariaho's blends into the overall production. I may not want to listen to it at home as I would Tristan, but it often makes for a better holistic production.

In the end, while Saariaho may not have achieved the sense of apotheosis as did Wagner and Messaien, L'amour de loin is a wonderful theatrical creation, especially married to this technologically rich and sympathetic production. The Met is to be congratulated for taking a risk on it (sadly, there were many empty seats in the house) and for devoting the resources needed to create an excellent experience in contemporary opera.

L'amour de loin has one of the better performance records for contemporary opera, with over ten productions following its premiere at the Salzburg Festival in 2000. Ever conservative, the Metropolitan Opera now gets to it 16 years later, but to its credit lavished a wonderful production on the opera. Through most of the opera the distant lovers, who learn of each other only via the Pilgrim who ferries back and forth (sort of a pre-internet dating site) are separated by the sea. In this production the separating sea is physically dominant, portrayed throughout by horizontal parallel laser light strings that completely occupy the massive Met stage from front to back, apparently about 5 feet above the stage itself, and even extending over the orchestra pit. Boats and birds portrayed in relation to this set are simple, almost cartoon-like in their spare design, increasing one's focus on the abstract sea:

These computerized lights can achieve a dazzlingly infinite range of color: sunset, storm, midday, etc. The chorus lurks below these lights (often with heads visible with vague amber lighting, like we are seeing them in the depths of the sea). But when they sing their heads pop up above the lights from below like singing mermaids as they act their main role as a Greek chorus admonishing the lovers. This was perhaps the most technically adept use of modern technology to suit and create an operatic mood that I have seen--here infusing the set with an ever-changing color palette that coordinated precisely with the music and plot. It's great to see that the Quebecois director and designer Robert Lepage has this brilliance in him, after the high-visibility failure of his recent Met Ring of the Nibelung with it's infernal machine that dominated the opera, stage, and action to poor use. Strikingly, in this opera the technical lighting-machine did not come across as a gimmick, overwhelming or diminishing the singers, who were often raised above the "sea" with a small elevated ship-like platform on a crane that reminded me of the old Myst games. Note the chorus' heads sticking above the water at left:

Composer Saariaho is one of a group of prominent Finnish composers prominent in contemporary music, and perhaps the most famous female composer now going. She has had a very visible New York season, with a recent concert by the New York Philharmonic of Sensurround pieces in the Park Avenue Armory (see my review here). She relies more on timbre and color than on melody and rhythm to achieve her purpose (similar to Debussy), and there were times, especially in the largely event-less first half, that my mind wandered, as it did at times in the NY Phil orchestra concert. Her music is very modernist in harmony without edginess--such edge might have been occasionally helpful for variety. The program notes described some use of medieval composition technique (e.g. organum with parallel fifths) but this was not at all obvious in the sound-world that emerged. When composers rely largely on color for expression, there is a great challenge in long pieces (like operas) to maintain interest--this challenge was faced in all four of the operas mentioned above. Of these, Wagner and Messiaen were not reluctant to use rhythm or the occasional big tune to bring an act to it's climax, e.g. the end of each act of Tristan or the end of St. Francis, but Debussy and Saariaho are less inclined to such extroversion. So how do they avoid boredom in a 2-3 hour opera?

I think that this opera succeeded best in the second half, when Jaufré journeys over the sea, at last meets his previously-imagined love, then dies. This included some plot elements that moved the opera forward--his dream of seeing her (wonderfully achieved with the soprano and a dancer-double emerging in and out of the water, lit like a hologram), a sea interlude akin to Debussy's La Mer or Britten's from Peter Grimes. Here there was more varying rhythm in the music, and the parallel sea-lights started heaving and moving vertically like waves to spectacular effect--the Met should have issued Dramamine! It was at these moments that Saariaho best achieved Wagner's concept of Gesamtkunstwerk--the unity of music, plot, lyrics, set, lighting to create one theatrical organism. These segments of the opera may have been the best I have seen of this ideal. Wagner's music tends to overpower the other elements, while Saariaho's blends into the overall production. I may not want to listen to it at home as I would Tristan, but it often makes for a better holistic production.

In the end, while Saariaho may not have achieved the sense of apotheosis as did Wagner and Messaien, L'amour de loin is a wonderful theatrical creation, especially married to this technologically rich and sympathetic production. The Met is to be congratulated for taking a risk on it (sadly, there were many empty seats in the house) and for devoting the resources needed to create an excellent experience in contemporary opera.

Comments

Post a Comment