Film Reviews: My Favorite Films, Plague Edition (Part 4): German Expressionism

Metropolis (1927)

Directed by Fritz Lang

M (1932)

Directed by Fritz Lang

Starring Peter Lorre

Germany between 1920 and 1932 was a grim place, even in the

years before the depression. Saddled with enormous debt after WWI, inflation

and unemployment were widespread, and income disparities were huge. Corporations joined the big business boom of

the 1920s while common people starved. This was fertile recruitment territory

for all sorts of political radicals, and its important to remember that, right

up until the Nazis were voted into power in 1932, they were in close competition

with Communists, monarchists, and everything in between as part of a fractured

political landscape. In film, Hollywood had become dominant as the producer of

popular, high quality silent movies that were watched worldwide. In those

years, the German film industry sought to carve out a niche that would

distinguish it from US products. It did so with a number of films called “expressionist”.

They featured non-realistic, overt, exaggerated human emotions, often set in

surreal landscapes or science fiction settings. Think of Nolde’s famous painting

“The Scream” and you will get the idea. This gave a new generation of German filmmakers

a chance to explore the art and visual style of film, as opposed to just plot

and entertainment. To some degree, their efforts started a cinematic trend that

continues to distinguish US and European film. A leader was Fritz Lang (1890-1976),

a Jewish director who was a star in the 1930s, then migrated to the US along

with many other prominent film people after Hitler ascended to power and Josef

Goebbels started to control film content in 1932-33. He made films in the US (the

best is the film noir detective thriller The Big Heat), but never quite

fit into the Hollywood star system that would not give him the exacting control

he sought. He was trained in architecture/engineering, and his films often show

amazing set design and innovative buildings and structures.

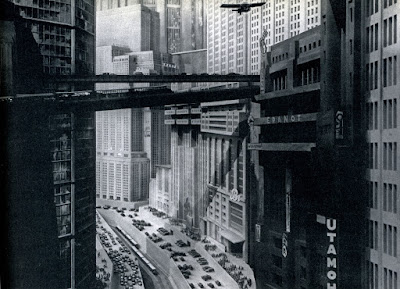

Metropolis was dreamed up after Lang visited New York

City in the mid-1920's, amazed by its towering cityscape. In this film he

creased a dystopian metropolis of the future. It is marked by severe income

disparity, with the elite living on high stories of skyscrapers, and the

workers toiling at ground level or below ground (just like NYC today). There

are elevated roadways, planes buzzing around, and infernal machines that

require repetitive, brutal toil by the workers—the workers become machines . If they stop, the city falls apart

(just like NYC today). The film depicts a worker revolt led by a female robot

devised by a mad anarchist scientist who wants to disrupt the status quo.

She later is engineered to take on the appearance of a real, virginal girl (named Maria!) and there are

interesting scenes where the false robot Maria dances lasciviously like a Busby

Berkeley chorus girl from the 30's and stirs up the aroused rich men. Besides the predictable virgin-whore subplot, Metropolis has a Pilgrim’s

Progress-like plot in which the lead character (the Teutonic Gustav Fröhlich) tours all the majesty and horrors of the Metropolis. It’s a bit melodramatic, and has slow spots in is 2 ½ hour length. But some of the visuals of the futuristic city are amazing, and the mad-science scenes where the robot is animated were the inspiration for the Hollywood Frankenstein movies of the 1930's. I was struck by first five minutes of the stunning opening, in which we see regimented oppressed workers marching to their galleys, then the blonde elite cavorting up above under architecture that looks just like what the Nazis would build 10 years later. In fact, if you merge these two extremes, you get Hitler’s later version of the class-less, regimented totalitarian state with everyone marching to the same drummer (him), seen vividly eight years later in Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935). But Hitler’s vision was a far cry from the optimistic ending of Metropolis when, after nearly destroying the city, the workers unite with the upper class to build a better society together.

By five years later, the optimism is gone. M was Lang’s first talkie, when sound in movies was still working out its technical issues. Made the year before Hitler took power, German society of the time was at its nadir economically and emotionally, and the film reflects this bleakness. It is a moving and brilliant film, as German society panics when a serial killer (Peter Lorre) murders several children. Then as now, there are witch-hunts, ineffective bureaucratic responses, and panic. The irony that Lang devises is that, frustrated by their failure to find the killer, the police team up with gangsters to find the killer (it turns out that public panic is bad for the gangsters’ liquor and drug trade). M addresses a central issue in criminology like no other film does—what do we do with a person who is without control of his violent impulses: try to medically treat them, or kill them? We are no closer to resolving this now and then, and Lang makes us face this dilemma. There is no easy resolution in M—we do not ever hear the court’s verdict, and we are left only with a scene of grieving mothers.

By five years later, the optimism is gone. M was Lang’s first talkie, when sound in movies was still working out its technical issues. Made the year before Hitler took power, German society of the time was at its nadir economically and emotionally, and the film reflects this bleakness. It is a moving and brilliant film, as German society panics when a serial killer (Peter Lorre) murders several children. Then as now, there are witch-hunts, ineffective bureaucratic responses, and panic. The irony that Lang devises is that, frustrated by their failure to find the killer, the police team up with gangsters to find the killer (it turns out that public panic is bad for the gangsters’ liquor and drug trade). M addresses a central issue in criminology like no other film does—what do we do with a person who is without control of his violent impulses: try to medically treat them, or kill them? We are no closer to resolving this now and then, and Lang makes us face this dilemma. There is no easy resolution in M—we do not ever hear the court’s verdict, and we are left only with a scene of grieving mothers.

Stylistically, the movie is all darkness, shadows, and

extreme lighting effects, plus acting from Lorre that evokes “The Scream”. We

see no murders, just the shadow of the killer, and a child’s ball and balloon bouncing

unclaimed to suggest what has happened. Check out this scene, beginning with a

nasal announcer talking about measures to ensure public safety, then cutting to

a scary dark screen in eerie, absolute silence--cars drive by on a street

without our hearing them, men rush by…but then a shrill whistle jars us at

21:43. Its as if the director is using light

and sound not to show us the world as it is or build conventional cinematic

tension, but instead as artistic effects to make an emotional (expressionistic)

point. The last 15 minutes are incredible, as the Nolde-like Lorre pleads for his life, saying he has no control over

his impulses. Again, there are great contrasts between the screaming Lorre and

the silent crowd, which eventually erupts into hatred that eerily portends the

evil of the Third Reich (note the Hitler-like cadence that the gangster-judge

develops after 1:43:30). This gangster crowd is about to condemn (and kill?)

him, when the police arrive…but notice how this is shown…we never see the police!

Lang was famous for exhibiting rigorous and absolute control, requiring many

retakes to get exactly the camera effect desired, a precision perhaps only

matched by Mizoguchi, who’s Sansho the Bailiff I reviewed last week. He precisely

chooses not to judge the murderer or provide an answer, leaving that to us. You

should see this movie—its one of my absolute favorites, and online on YouTube.

Comments

Post a Comment