My Favorite Films, Plague Edition (Volume 25): A Pioneering Indian Director

The Apu Trilogy

Directed by Satyajit Ray

Pather Panchali (1955)

Aparajito (1956)

The World of Apu (1959)

Satyajit Ray (1921-1992) was a pioneering and great Indian director, the first to win international awards, and one revered by other great directors such as Akira Kurosawa and Martin Scorcese. Prior to his work, Indian film was mostly dominated by fluffy musicals, such as the Bollywood films that are still popular. But with the premiere of Pather Panchali in 1955, both India and the world saw a lens turned on the complexities and beauty of their country, especially the qualities of rural India. The art of his films is to show the difficulties (death, disease, poverty) while maintaining an upbeat confidence in how people, with all of their flaws, still can still live fulfilling lives.

Ray was from an intellectual but poor family (a theme of these films). This was a common dyad in India then, since education was valued but not always rewarded with financial success. His mother pushed him into advanced studies (another theme of the films), where he studied Indian art, giving him the basis for the exquisite photography and visual impact of his films. After some mind-numbing jobs clerking (also reflected in the films) he began studying foreign films, and founded the Calcutta Film Society in 1947. His first films were inexpertly made, on small budgets. But he learned quickly and the world rapidly noticed his work, leading to awards at Cannes in the late 1950’s.

A unifying feature of these films is death, and how it is handled matter-of-factly, perhaps reflecting the culture of India. We see the death of Apu’s aged aunt and young sister in the first film, the death of his father (autobiographical) and then his lonely mother in the second film, and finally of his wife (off camera, during childbirth) in the third film. Each of the deaths feels oddly inevitable, as we see disease and difficult living conditions throughout all the films; in this environment early death seems quite expected. The director generally handles it that way, as we quickly see the characters move on with their lives, as happens often in real life. A general feature of these films is that conventional movie events that cause a Western movie to pause or exclaim (death, natural disaster) are just run-of-the mill here. This reminds me of a trek I did in the Karakoram in Pakistan, where a mudslide that buried a village was just another event, and our group calmly hiked around it and resumed the journey. In the end, the events that Ray focuses on as truly meaningful are interpersonal ones: the mother’s love for her son, the son’s neglect of his mother once he goes off to college, how two people fall in love after a hasty, arranged marriage, how Apu finds and bonds with his young son that he never saw after his wife died in childbirth years earlier. These events are, in Ray’s work, truly dramatic, and create a humanity that overrides all the other events. It’s wonderful to see a truly distinctive filmmaker who created his own style, and created a national school of film realism that endures to this day.

Directed by Satyajit Ray

Pather Panchali (1955)

Aparajito (1956)

The World of Apu (1959)

Satyajit Ray (1921-1992) was a pioneering and great Indian director, the first to win international awards, and one revered by other great directors such as Akira Kurosawa and Martin Scorcese. Prior to his work, Indian film was mostly dominated by fluffy musicals, such as the Bollywood films that are still popular. But with the premiere of Pather Panchali in 1955, both India and the world saw a lens turned on the complexities and beauty of their country, especially the qualities of rural India. The art of his films is to show the difficulties (death, disease, poverty) while maintaining an upbeat confidence in how people, with all of their flaws, still can still live fulfilling lives.

Ray was from an intellectual but poor family (a theme of these films). This was a common dyad in India then, since education was valued but not always rewarded with financial success. His mother pushed him into advanced studies (another theme of the films), where he studied Indian art, giving him the basis for the exquisite photography and visual impact of his films. After some mind-numbing jobs clerking (also reflected in the films) he began studying foreign films, and founded the Calcutta Film Society in 1947. His first films were inexpertly made, on small budgets. But he learned quickly and the world rapidly noticed his work, leading to awards at Cannes in the late 1950’s.

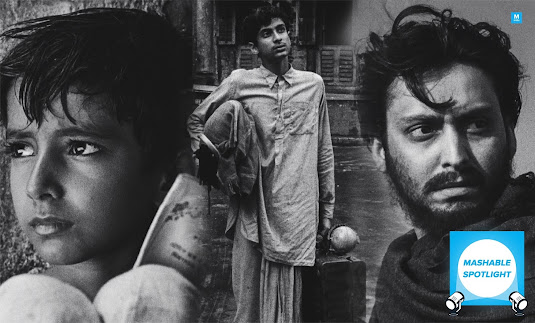

The Apu Trilogy was his first breakout success. The three films follow the life of Apu Roy and his family, and tracks many of the incidents of the director’s life. It roughly follows the plot of a famed Bengali novel Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road, 1929) by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay. In the three films we see four actors portray Apu, first as a small child, then at 10 and 17 years, and finally in his mid-twenties. Unlike films like Boyhood (2014) the director here does not make a lot of effort to find actors to portray Apu who match physically, vocally, or stylistically. He instead uses the plot, and the characters around Apu to create unity, especially the wonderful Karuna Banerjee as his mother Sarbajaya. The films are linked by recurring plot motives. Apu is steadily drawn between his love of the city, with its masses, culture, and intellectual stimulation, and his roots in an ancestral village, with its solidity, tradition, resilience in the face of natural disasters (Bengal is a difficult place to live), and link to ancestry. The connection between these worlds is the railroad, another motive of the films. In the first movie, the young boy wonders at the marvel of the railroad and watches it go by, much as young people do all over the world. In the second film, the railroad takes him from his village to an exciting new educational world at the university in Calcutta. And in the third film, the destitute Apu, struggling to stay afloat, moves with his new wife into a tiny apartment directly over the railroad station, constantly disturbed by the whistles and noise. This sequence is a nice metaphor for the plusses and minuses that technology (and the English) brought to traditional India—a mix of wonder, progress, and destruction.

The three films feel like a true epic, even though nothing really extraordinary happens to Apu (excepting his gaining entry into the university). Ray’s genius is in portraying daily common events at a leisurely pace, and yet having them all come together as an epic tale. Ray eschews common Western dramatic devices like Chekov’s gun—if a gunshot goes off in these movies, it does not necessarily portend something bad is about to happen, or that the shot will be important later. It is just part of life. Ray does use music (by the famed Ravi Shankar) to set the mood, and does use metaphor like the trains, or the scary storm that portends the death of Apu’s sister, seen here. But most often he creates connections by linking the characters to their surroundings, whether those be crowded alleyways and bathing ghats in Benares, or a decaying ancestral home in the village. The contrast between city and country is stark—the city scenes flit from place to place, as Apu discovers new places each day. The country scenes have serene stasis, with the camera moving slowly down roads and paths, just like one perceives in rural settings. We see on house, decaying slowly over three movies. We see one dirt path to the house, upon which any new person arriving is a major event. I have never seen the difference in pace between urban and rural so beautifully portrayed.

A unifying feature of these films is death, and how it is handled matter-of-factly, perhaps reflecting the culture of India. We see the death of Apu’s aged aunt and young sister in the first film, the death of his father (autobiographical) and then his lonely mother in the second film, and finally of his wife (off camera, during childbirth) in the third film. Each of the deaths feels oddly inevitable, as we see disease and difficult living conditions throughout all the films; in this environment early death seems quite expected. The director generally handles it that way, as we quickly see the characters move on with their lives, as happens often in real life. A general feature of these films is that conventional movie events that cause a Western movie to pause or exclaim (death, natural disaster) are just run-of-the mill here. This reminds me of a trek I did in the Karakoram in Pakistan, where a mudslide that buried a village was just another event, and our group calmly hiked around it and resumed the journey. In the end, the events that Ray focuses on as truly meaningful are interpersonal ones: the mother’s love for her son, the son’s neglect of his mother once he goes off to college, how two people fall in love after a hasty, arranged marriage, how Apu finds and bonds with his young son that he never saw after his wife died in childbirth years earlier. These events are, in Ray’s work, truly dramatic, and create a humanity that overrides all the other events. It’s wonderful to see a truly distinctive filmmaker who created his own style, and created a national school of film realism that endures to this day.

Comments

Post a Comment