Theater: Raw jail emotions mark Jesus Hopped the 'A' Train

Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train

Written by

Stephen Adly Guirgis

Directed

by Mark Brokaw

Starring

Sean Carvajal, Edi Gathegi, Ricardo Chavira, Stephanie DiMaggio

SignatureTheater

The

Pershing Square Signature Center

November

29. 2017

Jesus Hopped the A Train (2000), a

masculine, edgy exploration of criminality, race, and religion, is the second

play I have seen by Stephen Adly Guirgis. I also saw his later Pulitzer-winning Between Riverside and Crazy (2014) in

Washington DC a couple years ago, and was impressed by his ability to convey

smoldering, repressed anger and resentment hiding in middle class black lives.

Guirgis was born of Egyptian and Irish middle-class parents, and grew up in

Manhattan’s far upper west side, largely among black and Hispanic kids. He also

writes for TV cop dramas and acts in movies, TV, and stage. His nine plays

(including the problematically-named The Motherfucker

with a Hat) seem mostly driven by giving voices to the underclass of our

society, often mixing humor, profanity, and violence in variably successful and

disturbing combinations. Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train is no

exception. The play centers on two charged criminals in adjacent cells (onstage

cages on an otherwise blank set) on NYC’s Riker’s Island. The title comes from a vignette told by a prisoner about how he was miraculously saved from an onrushing subway train as a childhood dare-game of jumping on the tracks nearly went awry; it was as if Jesus himself were the driver of the train. The vignette encapsulates the plays themes of guilt, responsibility, and the role of belief.

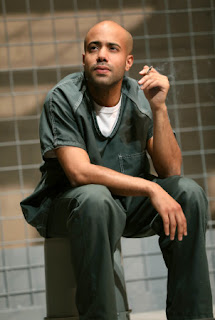

Both are charged with

murder, but they are otherwise quite different. Angel (a volcanic Sean

Carvahal) shot a Korean Moonie-type preacher who, in his eyes, had brainwashed

his friend and taken him away from him. Angel’s intent was to “shoot him in the

ass” as a warning, but the preacher later died of a heart attack during medical

treatment, so the DA charged Angel with first degree murder. Angel begins the

play with angry, scary, profane lashing out, but is in reality a naïve and

sensitive soul, half bravado and half guilt, crushed by the tragic outcome of

his “noble” act.

In contrast, Lucius, his cellmate next door (a wonderfully

creepy newcomer Edi Gathegi) is a psychopathic serial murderer who has found

Jesus and spends most of the play talking religion, confident that God has

forgiven him. While Lucius has committed the more heinous crime, he is more

certain of his own forgiveness by God, and tries to persuade Angel that he

should own up to his crime so that he, too, can achieve God’s forgiveness.

Thus

the playwright sets up one of several contradictions: the “angel” feels guilt

while “lucifer” is confident of his salvation. The playwright here may be

mocking the external certainty of some fundamentalist Christians, or perhaps

admiring it as a coping mechanism—his tone makes this uncertain. Now Angel is

awaiting trial, and Lucius is awaiting possible deportation to Florida for what

would likely be a death sentence. Things end badly for both characters, and the

playwright successfully makes us feel like we are caught up in a whirlpool of

dysfunctional criminal justice, in which randomness, racism, stupidity, and

economics all impede a honest and honorable outcome.

Where

playwright Guergis is most innovative is in how he does not allow us to relax

and fall into stereotypical court trial-based or capital punishment-based

plots. The two characters are multidimensional, simultaneously portraying

narcissism, stupidity, and ruthlessness alongside vulnerability, sadness, and

intelligence. Guergis is demanding of his audience; I sensed that many audience

membered wanted a black comedy, but were often put in the uncomfortable

position of laughing with a psychopathic killer. Guergis also resists linear

plotting, for example giving us the outcome of one character in an interlude

before we are finished hearing from them in the play, removing some of the “verdict”

tension that drives conventional plays and focusing us on the characters. I

admired how the playwright consistently defied my expectations to focus me more

on these two interesting characters.

But I

wished he had gone even farther. While 75% of the two-hour two act play focuses

on the interaction of the two prisoners, I wished that Guergis had been

courageous enough to make that 100%, creating a Zoo Story of the imprisoned. Both of the inmates’ roles are so

complex and interesting that a shorter, more concentrated play could have been even

more fascinating, in the model of O’Neill’s short expressionistic dramas. Instead,

there are subplots and monologues involving a guilt-driven white Public

Defender and two prison guards, one sympathetic, and the other abusively racist.

While this does allow some subplots about racism and brutality in prisons, lack

of due process in courts, and the conundrum of legal ethics vs. advocacy for

lawyers, I think these were not needed at the core of the drama, and I found

them mostly distracting. In particular, the insertion of the PD’s narrated details

of Angel’s trial make the play seem like it is going in the direction of a

conventional courtroom drama, even though we never leave the prison setting. Ditto

the ending monologue by the “good” prison guard Charlie, perhaps inserted to

show us at least one sympathetic character, but unnecessary to the plot and

distracting from the dark tone. These were both much less interesting characters

than the two prisoners, and could have been left out to good effect. On the

other hand, the other abusively brutal

prison guard does not talk much, and is useful as an intermittent foil to the

two prisoners—a sort of offstage looming threat. A three-character play would

have better focused us on Guergis’ superb gift for writing angry, smoldering

dialogue of underclass men, and tightened the play’s structure considerably. Guergis can certainly write an

effective conventional plot-driven play--witness the later Between Riverside and Crazy. But I

saw this play as a not-quite-experimental-enough exploration of street

language, raw emotion and religion, and a bit of a lost opportunity to produce

something truly revolutionary.

Comments

Post a Comment