Theater: Tracy Letts' Man from Nebraska is a comforting slice of life

Tracy Letts,

famous for the Pulitzer-winning August: Osage County

(2008) is a playwright whose characters reflect both the conservative stability

of his Midwest origins (Oklahoma) and the resultant disruption and pain to

families when inevitable change occurs, whether due to illness, bad luck, or, as in Man from Nebraska (2003), existential

angst. The play centers around Ken Carpenter, a solid Midwestern insurance

salesman who suddenly doubts everything—his religious faith, his marriage, his

values of hard work. Shockingly (to his family) he runs off to London, indulges

his artistic side, and falls in with counterculture types. The play ends

ambiguously, with Ken rejecting neither his Nebraska values nor his new

independence. The play does not have the pointed edge of August. The characters are gentler, more dull in a lovable sort of

way. Letts, who was inspired by Tennessee Williams, clearly emulated Williams’

operatic, overheated style four years later in August

(by the way, see the movie version with Meryl Streep—a memorable performance).

Not so much here. This play requires patience, as it spends much of the first

half showing normal Nebraska life in short vignettes: driving to see grandma in

the retirement home, eating dinner, getting ready for bed. Letts takes his time

in establishing the normality of it

all, creating a good counterpoint for what happens when Ken experiences his mid- to

late-life crisis. I admired how Letts shows that such disruptions are often

more calamitous for the family than for the individual. After all, they are

getting all the disruption without any exciting life-altering metamorphosis. The play rolls along gradually, and shows us life as we remember our past—a selective sequence of scenes memorable

enough in some way to lodge in our memories. Why only these scenes? Our memories

are capriciously selective for many reasons—to avoid pain, to emphasize

pleasure, to relive old insults. The first half of the play puts us in the

position of reconstructing the family history through these short scenes

separate in time.

The second

half of the play, mostly set in London where Ken is living out his new values and interests, is less successful. Unlike August

and most Williams plays, there is a lack of building tension, of a sense of

relentless inevitability that something big and dramatic will ensue. There is

nothing here like the apocalyptic family dinner scene from August, or the tragic climaxes of other working class plays like Death of a Salesman or A View from the Bridge . I think this was intentional, since

Letts’ point is that life is not really all that dramatic, and that we mostly

muddle along, somehow integrating change and stability, our own needs with our

loved ones’. While quite realistic, this makes for a less than compelling climax

to the play. That said, I admired how Man from Nebraska

projected a real warmth about traditional Midwestern values, without

condescension. It made me reflect on my own (now distant) Midwestern upbringing and

relatives; I felt a bit like a was among them all for a couple hours. In that

regard this is a great play for 2017, when we in the “intellectual elite” are

being asked to gain more understanding and empathy for the “working class”.

The production,

well-paced by director David Cromer, had very effective sound design by David

Kroger. In particular, the opening scenes of everyday life in Nebraska were

enhanced by sounds of Muzak, game shows, and pretty much nonstop sonic

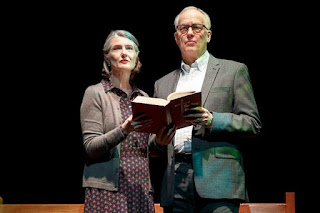

commercial clutter as at a shopping mall. Reed Birney (Ken) and Annette O’Toole

(Nancy, his wife) were wonderful, simultaneously portraying the stultifying

sameness of life and the repressed tensions underneath, without adding any false melodrama or artificiality. O'Toole managed to portray a staid, emotionally constricted, traditional woman without seeming evil or pitiful--I have met such people. All of the acting was very natural, in keeping with

the play. Even the climactic emotional conflicts were underplayed, with appropriate Midwestern reserve. Overall, this was a wonderful chance to eavesdrop on these normal characters for

a bit, reflect on how they are like us (or not), and exit without firm

resolution of where it all fits into the cosmos. While this makes Man from

Nebraska less exiting and memorable than August: Osage County, it should be accepted and appreciated for its

quiet take on Midwestern America.

Comments

Post a Comment