Music and Film: Mahler from NYPO; Toni Erdmann's excruciating papa-angst

Sometimes there are a lot of interesting things to do in New York

City. Here is a the first of a two part synopsis of an extended weekend of viewing in and

around Lincoln Center.

Thursday: New York Philharmonic at David Geffen Hall

Lera Auerbach (1973-) is a Julliard-trained Russian composer

mostly active in the west. Her NYx:

Fractured Dreams (Concerto No. 4 for Violin and Orchestra), 13 connected “sogni”

(dreams) for full orchestra, premiered this week. Like her somewhat vague

introduction onstage, and her poem upon which it is based (she is a bit of a

polymath, also into painting and performance art) was colorful, atmospheric,

and varied, but like so many compositions did not have a true forward thrust or

achieve a sense of momentum or destination. Her sound palette is similar to

that of Saariaho (see reviews) but without so much electronic music and

architectural use of sonic landscape. I did not really hear any connection to

NYC (despite the title). Soloist Leonidias Kavakos played convincingly, but

with a grim expression, and I worried that his shoulder length stringy

counterculture hair would get caught in his bow. The bowed saw soloist was

cool, introducing Sci-Fi tonalities into the dream. NYx was well paired with the following symphony, as both used

percussive string effects, dance episodes, and ghostly musical simulations.

After intermission, conductor Alan Gilbert conducted a buoyant performance of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony. This work is analogous to Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony: atypically light and even “fun”; follows, perhaps as a bit of a compositional breather, a period of intense innovative creativity (Beethoven Eroica Symphony and Rasumovsky Quartets, Mahler’s six movement Third Symphony, replete with chorus and soloist); and precedes further titanic works (Beethoven Fifth and Violin Concerto, Mahler Fifth and Sixth Symphonies). Gilbert achieved subtle flexibility and rubato in the first movement amble through the Austrian hills. Of course, this being Mahler, the nature stroll is interrupted by premonitions of doom, with foretastes of the brass funeral march in the Fifth Symphony, very clear in this performance. The orchestra played well. I wish some of the woodwinds and horns had been as responsive to Gilbert’s flexible treatment as were the strings. It felt like some of them were playing too forcefully, as if they were 1-2 symphonies ahead of the string section.

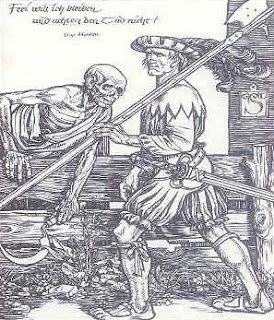

Performance note: In the second movement, concertmaster Frank Huang cleverly played the solos of “Freund Hein”, a fiddle-playing skeletal death-image.

Mahler aimed for an eerie effect by writing these solos for a scordatura violin tuned one whole step up from all the others. In this performance Mr. Huang's violin instead sounded very normal, at least from the front orchestra. Ditto on the 14 recordings I then listened to online, including several led by Mahler associate Bruno Walter, who certainly should know what Mahler intended. Sorry to be a heretic about my favorite composer, but it seems like a lot of trouble (e.g. tune and alternate between 2 violins) just to perform a special effect that does not really work.

Saturday Afternoon Cinema: Toni Erdmann

Toni Erdmann (2016) was favored to win the Oscar for Best Foreign Film this year, but lost in an upset. German director Maren Ade has a wicked sense of humor, and makes explicit in this film some of our greatest fears: What if we were naked in front of our work colleagues (metaphorically or actually)? What if we were chained to our parents? The film is at its best when it focuses on the struggles of Ines (the wonderful Sandra Hüller), a modern executive trying to balance being a professional businessperson with traditional obligations of family. In American films, this topic is usually treated via emotional struggles with difficult child-rearing issues, plus lots of screaming. Here our heroine must manage an eccentric (to put it mildly) father (the demonic Peter Simonischek) who, depressed after the death of his dog, stalks and annoys his daughter in Bucharest as she tries to negotiate a big corporate deal. This creates fabulously cringe-worthy moments that we all have experienced when our parents mix with our work or social life. What makes Toni Erdmann very German is 1. the lack of screaming and overt drama (all emotion is repressed in facial tension), and 2. the nature of the dilemma Ines faces. Family is a sacred obligation in Germany, and this tradition often conflicts with our modern, mobile, less connected world. Ms. Ade has wonderful comic timing and creativity, and creates some dynamite scenes (the inadvertently nude work party is hysterical). She needs to work on her pacing and editing, though. The film comes in at over 2½ hours long, and needed to be 45 minutes shorter, which would have better concentrated our uneasy laughter over the core father-daughter issues. But do see this film, especially if you are a fan of German culture and of angst-ridden comedy.

Comments

Post a Comment